Traveling Entertainment: The Chautauquas, 1915

In the early years of the twentieth century, before the days of radio and movies, an annual entertainment and cultural highlight for rural Vermonters was “Chautauqua Week.”

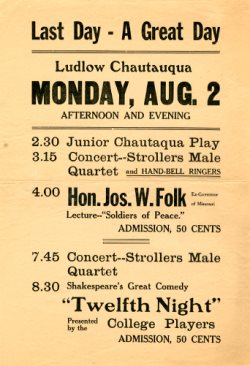

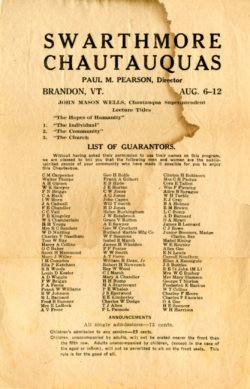

The tent Chautauquas were traveling groups that operated in many parts of the United States from 1904 to 1930, usually in villages and towns of 500 to 10,000 people. Each stop lasted approximately three to seven days during which audiences could enjoy a diversified program of lectures, music, drama, and humorous entertainment.

Oral history transcriptions

Click a name below for more information. All transcripts are in PDF format.

Background information

These circuit Chautauquas grew out of, but were apparently not connected to, the Chautauqua Institute, located at Chautauqua Lake, N.Y., a Methodist Sunday School training program of the late nineteenth century that blended inspirational oratory, education, and entertainment., Through booking agents of the early Lyceum days, the commercial circuit Chautauquas emerged by 1904 with a heavy entertainment emphasis. Those involved often regarded themselves as ministers of culture among country folk. The movement peaked in 1924 with thousands of American towns holding annual Chautauqua assemblies.

These circuit Chautauquas grew out of, but were apparently not connected to, the Chautauqua Institute, located at Chautauqua Lake, N.Y., a Methodist Sunday School training program of the late nineteenth century that blended inspirational oratory, education, and entertainment., Through booking agents of the early Lyceum days, the commercial circuit Chautauquas emerged by 1904 with a heavy entertainment emphasis. Those involved often regarded themselves as ministers of culture among country folk. The movement peaked in 1924 with thousands of American towns holding annual Chautauqua assemblies.

In Vermont, Lyndonville, Orleans, Hardwick, Northfield, Weston, and Springfield were among towns on the summer Chautauqua circuit. Held usually during July or August under a circus tent in an open field (as in Northfield) or on the local high school grounds (as in Springfield), the Chautauqua programs drew lager audience for the week-long programs involving daily afternoon and evening performances. A “season ticket,” usually costing $2.00, would guarantee seating for all performances.

Quality of these performances was uneven. Dorman B. E. Kent of Montpelier recorded in his diary his impressions of attending a Chautauqua week in August 1918. Kent was “much bored” by an afternoon lecture by a man who spoke “on cooking and gave demonstrations.” Nevertheless, the evening presentation of Israel Zangwill’s play, The Melting Pot, was “a very fine show indeed.” The next evening’s presentation of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado also “was fine.” On the third evening, “5 Canadian soldiers sang a few trench songs very much out of tune,” but they were followed by Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio, who “delivered an address which was a corker.” A Penobscot Indian “princess” who sang songs and danced also “was great!”

Chautauqua Week in Lyndonville, in August 1915 was described in a vivid letter written by Dorothy C. Walter shortly after the week’s events had ended. She described herself as “just like all the rest of the people in Lyndonville, Orleans, Hardwick, and other towns that have been having the meetings; I can’t talk of anything else!” With her sister, she attended “every afternoon and evening for six days and once Sunday morning.” In the audience were “folks whom you wouldn’t expect to be interest in the best music and lectures.” “That pleases me,” wrote Walter, daughter of Lyndonville’s newspaper editor, “for it means that the Chautauqua idea is working out as it is advertised to do and as it ought to do to be truly democratic. It ought to please those artists to know that one’s hired hand and one’s French neighbors recognize a good think when they hear it.”

Chautauqua Week in Lyndonville, in August 1915 was described in a vivid letter written by Dorothy C. Walter shortly after the week’s events had ended. She described herself as “just like all the rest of the people in Lyndonville, Orleans, Hardwick, and other towns that have been having the meetings; I can’t talk of anything else!” With her sister, she attended “every afternoon and evening for six days and once Sunday morning.” In the audience were “folks whom you wouldn’t expect to be interest in the best music and lectures.” “That pleases me,” wrote Walter, daughter of Lyndonville’s newspaper editor, “for it means that the Chautauqua idea is working out as it is advertised to do and as it ought to do to be truly democratic. It ought to please those artists to know that one’s hired hand and one’s French neighbors recognize a good think when they hear it.”

Of the week’s lectures, Walter particularly like several presentations on the theme of community improvement. “There are lots of things that need doing about town, but people don’t know about them till afterwards,” she wrote. For example, she enjoyed a speech by Dr. Edward Amherst Ott of Chicago who spoke on community building, the central idea of Chautauqua. Dr. Ott spoke on the benefits to towns of having “a department of the local board of trade to confer with young men and women ready to go into business and to tell them whether the town needed another lawyer or dentist or doctor or merchant and to point out the way to jobs that did need doing.” Ben Lindsay, the famous “children’s judge” from Denver, Colorado, spoke on ways of community building through improved relations between parents and children; and a business college president lectured on community building from a business point of view.

There was something for everyone at Lyndonville. Walter recorded that audiences were treated to music from separate male and female quartets; a man who presented vocal selections from The Barber of Seville (who “didn’t seem to be very much pleased when the little folk on the front seats roared and laughed”); an Italian band; and banjo, xylophone, cornet, and piano instrumental performers. They heard a lecture on ethics (“Really it was on selfishness”) from a University of Pennsylvania professor; a debate on the worth or woman suffrage; an anti-war lecture from a woman whose announced topic was about birds; and a lecture “on the Mormon kingdom of today,” which held the “large audience breathless through several hours.” A special treat was the production of Much Ado about Nothing before “a large and enthusiastic crowd.” She described the production: “They do not make any attempt at scenery but play the plays as Shakespeare meant them to be played, with no breaks at all. They have money to put into costumes on account of not lavishing it in scenery. The best of it is that they are all good. They don’t try to have starts as so many companies do.”

Northfield had its first of several annual Chautauquas in 1915. Springfield’s began about 1918; in Weston the events were still common in the 1920s; in Hardwick they apparently were annual events from around 1915 to the early 1920s. By the end of the decade, however, other forms of entertainment competed for the Chautauqua audience. For example, by 1930, eleven theaters had begun showing movies (most of them on a daily basis) in representative communities of Orleans and Rutland, and summer Chautauquas were reported that summer in only two communities. The era of the circuit Chautauquas was brief, but it eased the insularity of the lives of some rural Vermonters and was a source of excitement and stimulation for many more.

—Gene Sessions

Further reading

Dorman B. E. Kent, Diaries. In Dorman B. E. Kent papers, Vermont Historical Society library, Doc 235.

Dorothy Charlotte Walter. “Chautauqua Week in Lyndonville: A Description Written in 1915.” Vermont History 38 (1970): 200-203.

Citation for this page

Woodsmoke Productions and Vermont Historical Society, “Traveling Entertainment: The Chautauquas, 1915,” The Green Mountain Chronicles radio broadcast and background information, original broadcast 1988-89. https://vermonthistory.org./traveling-entertainment-chautauquas-1915