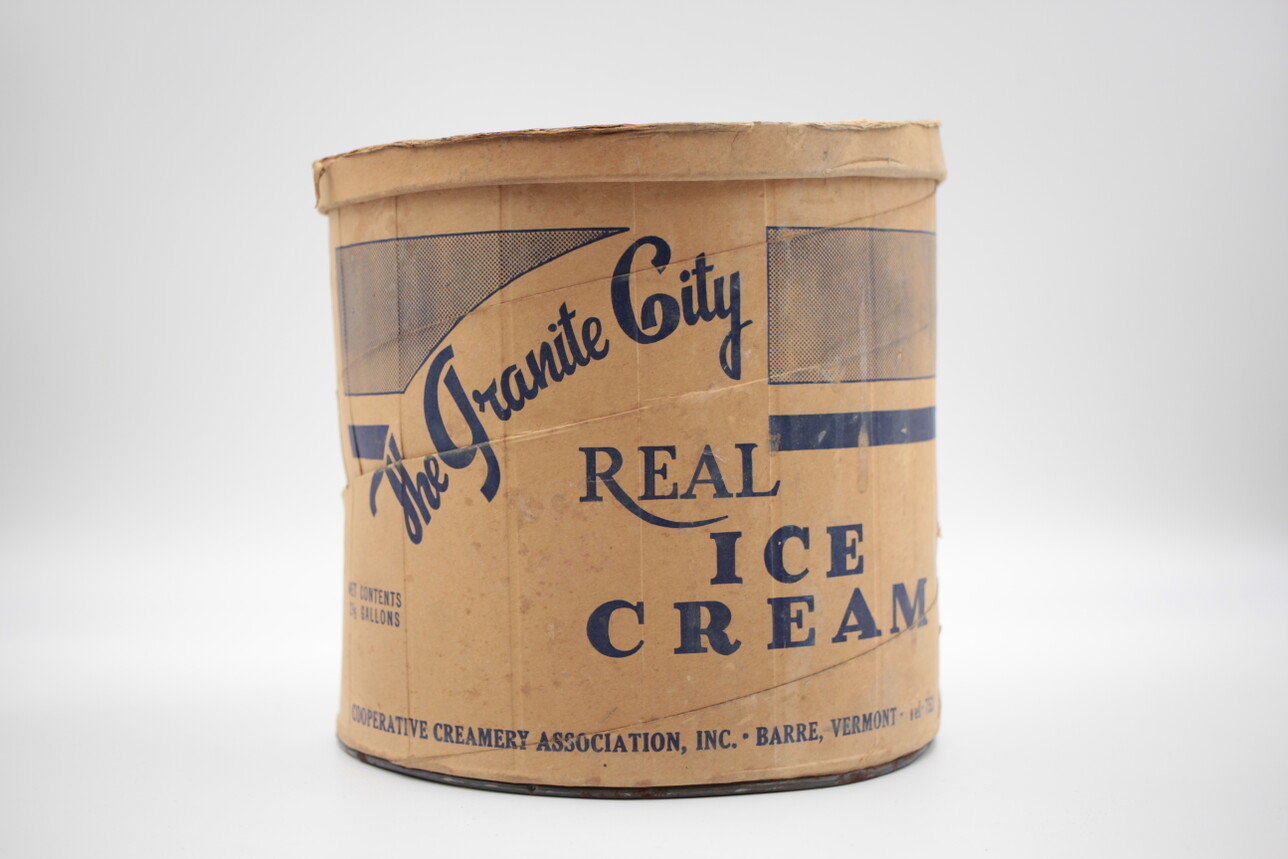

The Granite City’s Real Ice Cream

By Kate Phillips

A1926 Barre Daily Times advertisement for Real Ice Cream broke down the treat’s appeal into five points, lauding the sanitary conditions of its production, the quality of its cream and fruit ingredients, its status as a “pure health food,” and most of all, the fact that “it is made by a local concern, owned and operated by local people.” While an earlier ad promised eaters that Real Ice Cream would “bring you luck for the days to come,” much of its marketing focused on the circumstances of its production. Real Ice Cream, whose 1920s flavors included maple walnut, grapenut, and banana nut (as well as the classic Neapolitan), was a product of Barre’s Granite City Cooperative Creamery Association, a cooperative of dairy farmers formed in 1920.

The cooperative model first took root in Vermont in the late 1840s with the founding of protective unions. These were collectives of farmers, craftspeople, and other producers, which operated essentially as both buying clubs and labor unions. The preamble to the 1850 by-laws of Jamaica, Vermont’s Division No. 154 of the New England Protective Union (in the VHS library collection) summed up the revolutionary nature of these organizations, pointing to conditions that allow “the speculator and monied power to seize upon the products of the laboring classes and… fix upon them a high and fictitious price, thereby putting it many times out of the power of the producer to share in the products of his own hands.” They vowed to unite “to remove this unnatural, unsafe, and unsound state of things and to put these common blessings within reach of all by dispensing with all unnecessary and useless functionaries in the several departments of mercantile, civil, and social life.”

Though the protective unions appear to have died out by the end of the Civil War, the ideals served as a model for both the producer and consumer cooperatives that would come to flourish in Vermont. A 1915 piece of state legislation laid out the legal framework for organizations calling themselves cooperatives, which included such principles as one vote per shareholder and the distribution of equal dividends at the year’s end. It is at this point that Vermont becomes a center of cooperative activity: cooperative creameries, food co-ops, credit unions, electric co-ops, and more.

Cooperative creameries allowed small dairy farms to pool their resources to process, market, and transport milk. The development of retail and then personal freezers made ice cream a viable commercial product — one that provided creameries with an outlet for excess fluid milk (beyond cheese and butter).

This photograph is undated, but the women’s fashion and the delivery truck model suggest it was taken in 1926, just before the flood of 1927 damaged the Real Ice Cream production facility. After repairs, Real Ice Cream remained a Barre staple for decades, outlasting the Cooperative, which closed in 1969. Another 1920s ad claimed that “Roosevelt once said that support given to a local industry was the equivalent to a rise in wages to every man in the community. Moral — Eat Real Ice Cream, manufactured by our local Cooperative creamery ice cream plant.”

The moral of today’s story? Go visit your local creemee stand!

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2022 issue of our member magazine, History Connections. To get it and support the Vermont Historical Society, sign up as a member.