Gateway to the Revolution: Lake Champlain's strategic significance during the colonial era

At the dawn of the Holocene, the glaciers that covered North America began to retreat, leaving in their wake an inlet that stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to Ottawa to what’s now known as the Champlain Valley. As the sea retreated in the thousands of years that followed, Lake Champlain and the far-reaching forested lands were appealing to the first Paleo-Indians who arrived around 13,000 years ago. They called the lake Bitawbagok, or “The Waters in Between,” and found it to be a useful route that allowed for easy access to trade far beyond the valley.

As European colonizers began arriving in the fifteenth century, amongst the challenges they faced was the landscape: endless dense forests covering mountain ranges that terrified the Puritan settlers and made travel across the land difficult and dangerous. Rivers and watersheds became essential routes into the continent.

The elements that made Lake Champlain so appealing to its inhabitants over the millennia made it a critical strategic corridor for the various sides that fought during the American Revolution and drew the settlers living in the New Hampshire Grants into playing a critical role in the conflict. Writing in Lake Champlain: An Illustrated History, Russell Bellico notes that “no other lake in America has experienced the breadth of military activity as has Lake Champlain,” and that “the pivotal battles fought in the Champlain Valley determined the fate of the continent and political destiny of America.”

European and Indigenous inhabitants understood the importance of these waterways. The French set up a series of fortifications along the Richelieu River Valley starting in 1665, and as they and England vied for control of the region during the Seven Years War, each relied upon the lake and neighboring waterways to move goods and troops throughout the region. In We Go as Captives, Neil Goodwin underscored the region’s importance: “The Hudson River-Lake Champlain-St. Lawrence River-Great Lakes waterway was considered the most important transportation and communications route in North America,” a straight shot from Canada into the heart of American territory.

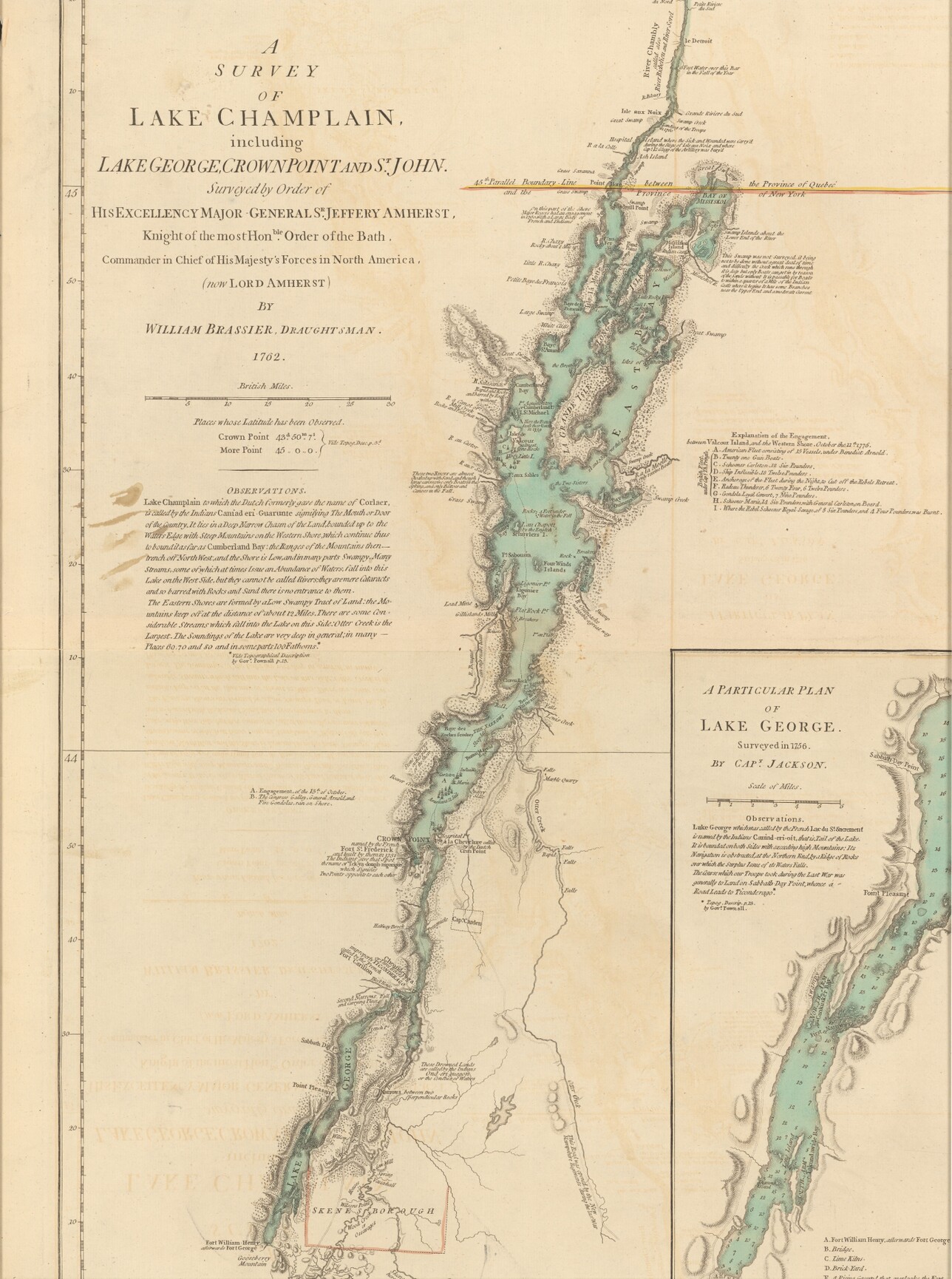

A survey map of Lake Champlain, 1762

As the American colonies prepared war in 1775, its leaders recognized Lake Champlain’s importance early on. In March 1775, John Brown, a lawyer from Pittsfield, MA, who was dispatched to Montreal to gauge support from their northern neighbors, reported in a letter that Canada wouldn’t join the American cause, and that “the Fort at Ticonderoga must be seized as soon as possible, should hostilities be committed by the King’ s Troops. The People on the New-Hampshire Grants have engaged to do the business and in my opinion are the most proper persons for the job.”

After the attacks in Lexington and Concord in April, Connecticut officials committed funds for an attack against Ticonderoga, while Massachusetts officials dispatched Captain Benedict Arnold to mount an invasion. The British were also well aware of the lake’s strategic importance. In April 1775, Colonial Secretary Lord Dartmouth, issued orders to General Thomas Gage in Boston that all forts in North America were to be reinforced.

His orders arrived too late. Ethan Allen and members of the Green Mountain Boys, along with Arnold and Massachusetts volunteers, crossed Lake Champlain and captured Ticonderoga on May 10th, while to the north, Seth Warner and his men captured Crown Point. A third contingent captured the town of Skenesborough the next day. Capitalizing on the assaults, Arnold and a small group of his men took a ship up the lake to St. Jean, “where he seized its small garrison and the heavily armed British sloop Enterprise,” which Michael Sherman, Gene Sessions, and P. Jeffrey Potash note in Freedom & Unity: A History of Vermont, “gave the patriots total control over the lake.”

As the Revolution ignited, control over the lake would be essential, as an invasion could split the colonies into two. After the Americans mounted a disastrous invasion of Canada in the winter of 1775, the British launched their own in 1776. General Guy Carleton led his fleet of 33 ships into Lake Champlain on October 9th with the intention of reaching the Hudson Valley. They were met by Arnold and his smaller flotilla off Valcour Island on October 11th, and after a violent battle that inflicted heavy damage on both sides, Arnold retreated down the lake but was able dissuade Carlton from continuing.

It was a temporary reprieve: General John Burgoyne led a larger force south the following year, occupying Crown Point on June 30th and advancing on Ticonderoga on July 2nd. Outnumbered, the American forces ceded control of the forts but hampered Burgoyne rear-guard actions and battles throughout July and August, ultimately leading to his defeat at the Battle of Saratoga in September.

After the Saratoga campaign stalled and failed, both American and British forces continued to fight around Lake Champlain. The British opted to abandon both Fort Ticonderoga and Crown Point in November 1777, but they continued to launch attacks against the region through the end of the war.

After the American Revolution ended, Lake Champlain proved to be a lucrative commercial route for the new United States and Vermonters, and its strategic importance returned nearly three decades later during of the War of 1812, when British forces once again attempted to make their way into the U.S. by way of Lake Champlain, only to be repulsed after the Battle of Plattsburgh on September 11th, 1814. It was the final invasion of the country, and with its conclusion, Lake Champlain’s time as a battleground came to an end.

Now, the only physical reminders of the nearly three centuries of conflict rest at the bottom of the lake, a reminder of the importance that its waters once held for the fate of the nation.

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of our member magazine, History Connections. To get it and support the Vermont Historical Society, sign up as a member.