Revolutions of Thought in Museum Spaces

By Danielle Harris-Burnett

For many, the Revolutionary War takes on mythic proportions. As we approach the 250th commemoration of the Declaration of Independence, historians and teachers alike are reexamining our relationship with the conflict. The 250th is an opportunity to reexamine our complex relationship with the past and ask questions about what we can accomplish in the next 250 years. How do we reconcile “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” with Thomas Jefferson’s ownership of human beings, or talk about Vermont’s role as an independent republic during the war? The Vermont History Museum is the place to ask those questions with students because of the interaction with physical objects.

When teaching about Vermont in the late 1700s, we can often fall into a trap of talking about Vermont exceptionalism. If we are to understand the United States as an ongoing experiment in democracy, then Vermont is one of its many testing sites. History rarely gives us a straightforward answer. Yes, the Green Mountain Boys formed a militia group to split from New York and New Hampshire. No, this was not exclusively because they were a group of rugged individualists. Yes, Vermont abolished adult slavery in its 1777 constitution. No, this does not mean formerly enslaved people like Jeffery Brace received a warm welcome after moving to Vermont—or that other Vermonters did not own enslaved people. Our predecessors led their own complicated lives, just as we do today, we can’t expect them to fall neatly into one category.

These are all questions that historians are grappling with. So how do we condense these massive and complicated ideas of an ongoing revolution into a museum exhibit?

The Freedom and Unity exhibit at the Vermont History Museum in Montpelier explores the role that Vermonters played in the Revolutionary War, and in one section, visitors can explore a recreation of the Catamount Tavern, where members of the Green Mountain Boys would meet.

This section has changed since it first opened in 2004. It originally featured a mannequin of Dr. Samuel Adams, a sympathizer to New York’s claims over the territories granted by New Hampshire who was publicly humiliated by members of the Green Mountain Boys in 1774. When the exhibit was updated and the mannequin removed to save space, we replaced it with a label that describes Adams’ story. Its removal demonstrated some changing attitudes towards teaching the past; rather than making a spectacle of a humiliating event, we now prompt visitors to explore the tavern on their own and put themselves in this historic moment. What types of conversations would they have around the table? Would they find Adam’s punishment and other similar events deserved or excessive? This immersive environment helps to shape the opinions that visitors might form.?

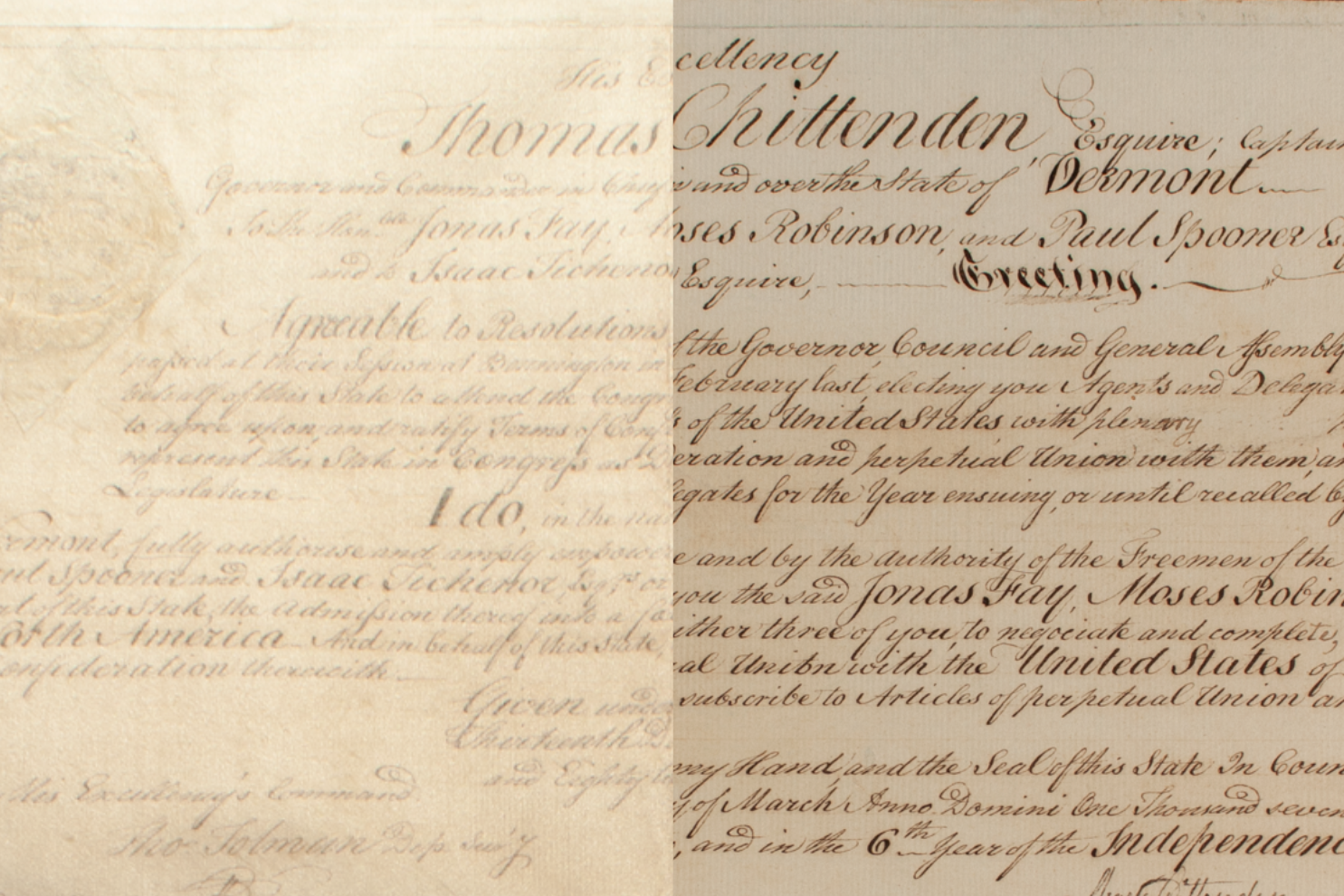

Similarly, objects can play a role in helping convey these complicated situations for students and visitors alike. VHS holds many physical objects from the Revolutionary War and its aftermath in our collection, such as musket balls, sabers, teacups, and uniforms, all of which are tangible reminders of the past. With the proper context, they provide a window into the minds and culture of a nation seeking connections to their origins and past. For example: a powder horn used by John Carpenter while serving in the Vermont militia at Fort Defiance in Barnard shows scenes of wildlife and possibly of the Royalton Raid of 1780. Through this item, we get a first-hand interpretation of a complicated moment in Vermont’s history.

As we move into the 250th commemoration, it’s important as educators to recognize the value of encouraging students to think about our relationships with the past. Visitors and students may expect that they already know the main story beats that make up the Revolutionary War. Through these objects and spaces, history educators provide the necessary scaffolding for learners to form their own analysis. After all, our shared history is not a roadmap, but a record of where we’ve already been.

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of our member magazine, History Connections. To get it and support the Vermont Historical Society, sign up as a member.