New England Mill Workers

These materials were originally created in 1999 as a supplement to the exhibit Generation" of Change: Vermont 1820-1850"

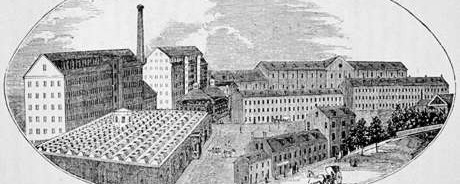

In 1814, the Boston Company built America's first fully mechanized mill in Waltham, Massachusetts. Nine years later, the company built a complex of new mills at East Chelmsford, soon renamed Lowell in honor of the company's founder, Francis Lowell. With the production process fully mechanized, the principal limitation on the firm's output was the availability of labor, and here the company made its second innovation: it began to recruit young farm girls from the surrounding countryside. In order to attract these women and to reassure their families, the owners developed a paternalistic approach to management that became known as the Lowell system.

The mill workers were housed in clean, well-run boardinghouses, were strictly supervised both at work and at home, and were paid unusually good wages. The farm girls responded with enthusiasm. They soon became renowned as excellent employees, and their lively self-improvement program (including a literary magazine) drew international attention. Few of the Lowell women worked more than a few years, but for every one who returned home to marry, two new ones appeared. By the 1830s, the Lowell system had become a national symbol of the fact that in America, humanity could go hand in hand with industrial success.

Even at the pinnacle of its renown, however, conditions in Lowell had begun to deteriorate. In 1834, an economic downturn led to the mills' first wage cuts. In the 1840s, managers instituted a speedup, requiring higher and higher output for the same hourly wage. The women formed the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association and tried to appeal to their employers and then to the state legislature through petitions. These led to state investigations in 1845 and 1846, but little changed. After 1848, conditions deteriorated further, as New England's textile industry began to suffer from overexpansion. Seeking cheaper labor, the mill owners turned increasingly to Irish immigrants and in the process discontinued the management policies they had devised to attract workers from the farms. By the 1850s, the Lowell system had been abandoned.

A Vermont Girl Goes to Lowell

Mary Paul, daughter of Bela and Mary, grew up in Barnet and Woodstock, Vermont. Beginning at age 15 until she was married at 27, Mary moved quite a bit in search of work. Between 1845-1850, she joined thousands of young women in the textile mills in Lowell, Massachusetts. Following this employment (1852-1854), Mary partnered with another seamstress in Brattleboro, Vermont to make coats. In 1857, she married Isaac Guild, the son of her former Lowell boarding house manager, after living in an utopian community in New Jersey and working as a housekeeper in New Hampshire. The newlyweds moved to Lynn, Massachusetts, where Isaac worked in the marble industry and Mary raised two daughters.

Mary was close with her father and maintained steady correspondence with him while she was away from her family. These letters provide invaluable information about the contrast between the traditional ideals of womanhood and the reality for many ordinary women. Women, traditionally, were expected to be wife and mother. Their domestic role was characterized by submission and dependence on men, first her father, then her husband. Mary Paul, however, represents the individual economic independence desired and needed by many women. She knew she could financially do better for herself in Lowell than in rural Vermont. Her frequent letters and constant inquiries about family members show her strong familial ties.

The following are all excerpts taken from letters written by Mary Paul to her widowed father Bela Paul, from 1845-1857. Read these selections to learn firsthand about the life of the Lowell mills and the changing roles of women during this period.

Sat. Sept. 13, 1845; Woodstock, VT

I want you to consent to let me go to Lowell if you can. I think it would be much better for me than to stay about here. I could earn more to begin with than I can any where about here. I am in need of clothes which I cannot get if I stay about here and for that reason I want to go to Lowell or some other place.

Nov. 20, 1845; Lowell, MA

I started for this place at the time I talked of which was Thursday. … Did not stop again for any length of time till we arrived at Lowell. … We found a place in a spinning room and the next morning I went to work. I like very well have 50 cts first payment increasing every payment as I get along in work have a first rate overseer and a very good boarding place. I work on the Lawrence Corporation. Mill is No. 2 spinning room.[1] …I think of staying here a year certain, if not more.

Dec. 21, 1845; Lowell, MA

Perhaps you would like something about our regulations about going in and coming out of the mill. At 5 o'clock in the morning the bell rings for the folks to get up and get breakfast. At half past six it rings for the girls to get up and at seven they are called into the mill. At half past 12 we have dinner are called back again at one and stay till half past seven .[2] I get along very well with my work. I can doff as fast as any girl in our room. I think I shall have frames before long. The usual time allowed for learning is six months but I think I shall have frames before I have been in three as long as I get along so fast. I think that the factory is the best place for me and if any girl wants employment I advise them to come to Lowell.

Apr. 12, 1846; Lowell, MA

You wanted to know what I am doing. I am at work in a spinning room and tending four sides of warp which is one girls work. The overseer tells me that he never had a girl get along better than I do and that he will do the best he can by me. I stand it well, though they tell me that I am growing very poor. I was paid nine shillings a week last payment and am to have more this one though we have been out considerable for backwater which will take off a good deal .[3] The Agent promises to pay us nearly as much as we should have made but I do not think that he will. The payment was up last night and we are to be paid this week .[4] I have a very good boarding place have enough to eat and that which is good enough. The girls are all kind and obliging. The girls that I room with are all from Vermont and good girls too. Now I will tell you about our rules at the boarding house. We have none in particular except that we have to go to bed about 10 o'clock. At half past 4 in the morning the bell rings for us to get up and at five for us to go into the mill. At seven we are called out to breakfast are allowed half an hour between bells and the same at noon till the first of May when we have three quarters [of an hour] till the first of September. We have dinner at half past 12 and supper at seven.

Nov. 5, 1848; Lowell, MA

I was unable to get my old place in the cloth room on the Suffolk or on any other corporation. I next tried the dressrooms on the Lawrence Cor[poration], but did not succe[e]d in getting a place. I almost concluded to give up and go back to Claremont, but thought I would try once more. So I went to my old overseer on the Tremont Cor. I had no idea that he would want one, but he did, and I went to work last Tuesday—the same work I used to do.[5]

It is very hard indeed and sometimes I think I shall not be able to endure it. I never worked so hard in my life but perhaps I shall get used to it. I shall try hard to do so for there is no other work that I can do unless I spin and that I shall not undertake on any account.

Jul. 1, 1849; Lowell, MA

My health has been pretty good though I have been obliged to be out of the mill four days. I thought then that it would be impossible for me to work through the hot weather. But since I think I shall manage to get through after a fashion. I do not know what wages I am to have as I have not yet been paid but I shall not expect much, as I have not been able to do much, although I have worked very hard.[6]

Nov. 6, 1853; Brattleboro, VT

I am getting along in the shop as usual. Have been making coats for a few weeks. I like it pretty well and am hoping to do better than on smaller jobs. I have plenty to do all the time.

These letters are currently in the collection of the Vermont Historical Society. They can also be found in transcription in Farm to Factory: Women's Letters, 1830-1860, Thomas Dublin, ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993). The footnotes have been extracted from Farm to Factory for the purpose of offering explanation to Mary Paul's comments about life in Lowell.

Footnotes to Mary Paul's letters

1. Surviving payrolls reveal that Mary Paul earned $0.30 per day in her first month in the mill, making $1.80 per week, or $0.55 above the cost of room and board. Lawrence manufacturing Company Records, Vol. GB-8, Spinning Room No. 2, Nov. 20, 1845.

2. Mary is outlining the winter schedule, when operatives took breakfast before beginning work. In the summer months, as the next letter indicates, work began at 5:00 A.M. and operatives had short breaks for breakfast and dinner during the working day.

3. Mary tended four sides of warp spinning frames, each with 128 spindles, the normal complement for spinners in these years. She quoted her wages in English currency, though she was undoubtedly paid American money, nine shillings being equal to $1.50. As in the earlier cases, Mary is referring to her wages exclusive of room and board charges. "Backwater," mentioned here, was a common problem in the spring, when heavy run-off due to rains and melting snow led to high water levels, causing water to back up and block the waterwheel. Mills often had to cease operations for several days at a time. The April payroll at the Lawrence Company indicates that Mary worked only fifteen of the normal twenty-four days in the payroll period.

4. It was standard practice to post on a blackboard in each room of the mills the production and the earnings of each worker several days before the monthly payday, to enable operatives to see what they would be paid and to complain if the posted production figures did not agree with their own records of the work.

5. The "dressroom" mentioned here would be a dressing room in the mill where warp yarn was prepared for the weaving process. Generally speaking, more experienced women worked in the dressing room, wages and conditions of work being considerably better there than in the carding and spinning rooms.

6. The fact that Mary Paul does not know what her wages will be suggests that she has recently returned to the mills after a period of absence. Since earnings were based on piece wage rates, it always took a new worker a month or two to determine exactly how much she could expect to earn.