Bonnie Clause on Edward Hopper and his time in Vermont

With For the Love of Vermont: The Lyman Orton Collection on display at the Vermont History Museum in Montpelier, we wanted to look at some additional parts of Vermont's art history.

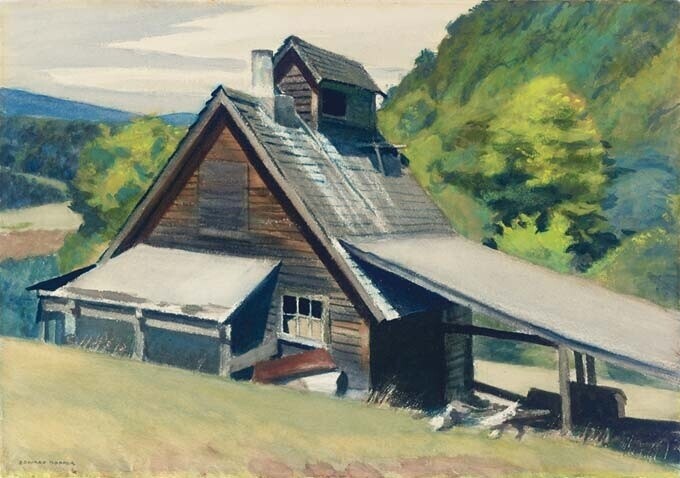

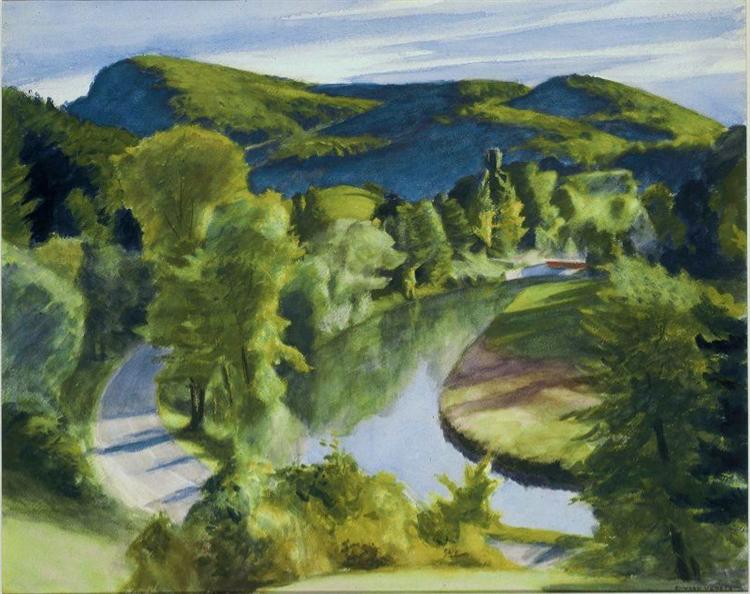

Vermont has long been home, or at least inspiration to artists of all stripes, from all over the world. One such artist was American painter Edward Hopper, who's probably best known for works like "Nighthawks." He was born in and spent most of his time in New York, but for two summers, he made the trip up to Vermont and produced a handful of watercolors, including "Barn and Silo, Vermont" and "First Branch of the White River". That period attracted the attention of author Bonnie Clause, who wrote Edward Hopper in Vermont in 2012, which was accompanied by an exhibition at Middlebury College in 2013. Clause's book is unfortunately out of print, but you can find it online for free via Project Muse.

We spoke with her about Hopper and his time in Vermont.

To start, can you tell us about your background? How did you first encounter Edward Hopper’s artwork?

I’m originally from a small town in New York State, coincidentally not too far from where Edward Hopper grew up—generations earlier—in Nyack, on the Hudson River. When I enrolled in an art history course at Barnard College in New York City in the 1960s, I discovered the city’s fabulous art museums and the wonderful collection of Hopper’s paintings at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Hopper immediately became one of my favorite artists, as his paintings beautifully captured scenes that I knew—the city streets, buildings, and bridges that then surrounded me and the gabled houses of the Hudson River Valley towns that I knew from my youth. Many years later, when my partner, Mike Hogan, and I built a new home on a hillside in Royalton, I was amazed to discover that Hopper had spend time in Vermont. Most surprising, I learned that when he and his wife, Josephine Nivison Hopper, stayed in South Royalton during the summers of 1937 and 1938, he painted watercolors of places we passed every day on our drive down to the post office.

Again, and unexpectedly, I found images in Hopper’s paintings of places that I knew and loved. I found that very little was known about Hopper’s time in Vermont, and this led to my research—and eventually to my book, Edward Hopper in Vermont, published in 2012 by the University Press of New England. I found that researching and writing the book also gave me the welcome opportunity to learn about Vermont life during the 1930s, so that I could present the Hopper story within the appropriate historical context.

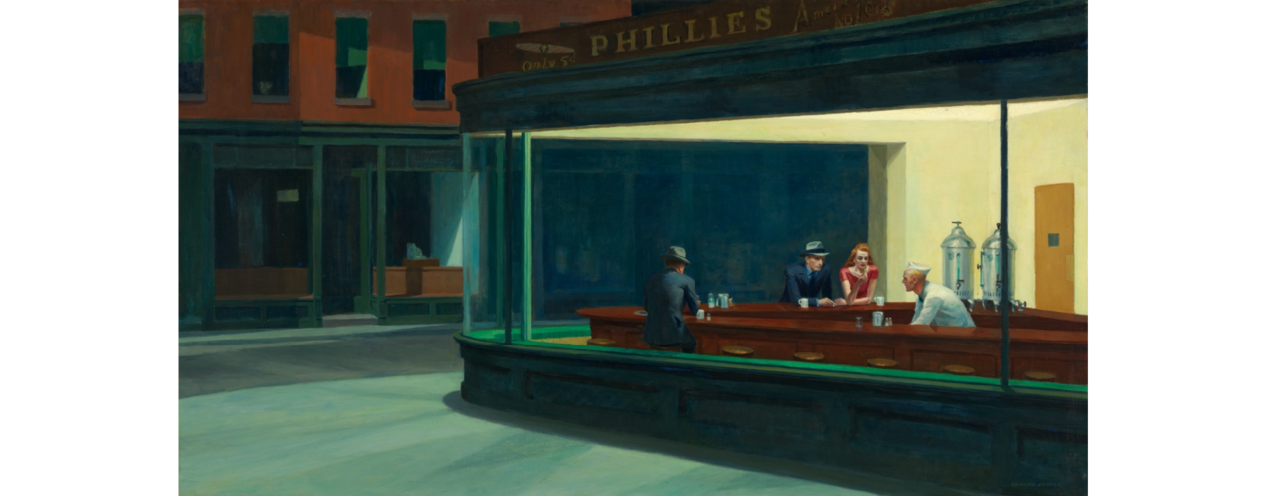

Hopper is regarded as one of foremost modern American artists, and he’s best known for paintings like Nighthawks and Early Sunday Morning. What do you think is behind the lasting appeal of his work?

Hopper’s most famous paintings have enormous popular appeal because they capture scenes that we recognize from the world around us, evoking memories of experiences and associations with places from our past and present. His works are “accessible,” easy to understand at first glance, yet inviting contemplation on a deeper level. They are like stills or frames from movies, slices from lives that could be our own, views that we may have seen in passing from the windows of cars or trains.

Even those who claim to know nothing about the artist will respond with recognition to the title and image of "Nighthawks," depicting a classic American diner populated by a late-night cast of characters. It is a familiar scene that also has an air of mystery and intrigue—who are these people, and what are their relationships?—that invites us to speculate and create our own stories. Paintings like "Early Sunday Morning," depicting a row of red brick facades with blank windows, invite us to look at everyday architecture with the artist’s eyes. They display Hopper’s masterly treatment of the nuances of light and shadow, drawing and holding our attention as they show us the artistry in the mundane.

Hopper was in born New York and painted "Nighthawks" and "Early Sunday Morning" in New York City, where he and Jo maintained their permanent residence. In 1937 and 1938, he spent time in South Royalton, which you cover in your book Edward Hopper in Vermont. What drew him to the Green Mountain State?

In the summers, Edward and Jo left New York for their small home in the dunes of South Truro, on Cape Cod in Massachusetts. After some time there, Edward would become restless and unproductive and need a change of scene. With urging from Jo—who was also an artist—the Hoppers would drive to other areas of New England in search of new subjects to paint.

Their first foray into Vermont was in 1927, when Edward made several small watercolors of barns; on subsequent brief trips, he painted a few landscapes with hillsides and dirt roads. In these works, Hopper seemed to be searching for a compelling subject, and it was in South Royalton in 1937 that he found it: the White River. That he was seeking a Vermont river to paint was suggested by Hopper himself, when he later wrote: “The valleys of the branches of the White River and the White River valley itself are, to me, perhaps the finest in Vermont.”

The result was a series of seven watercolors of the White River made over the course of two extended summer sojourns. These works show the White River at diverse locations between Bethel and Sharon, at different times of day and under different weather conditions. They evidence Hopper’s ability as a master of observation as well as of watercolor technique.

What was his experience here like, and how did the landscape and people impact his painting style?

The Hoppers’s experiences in South Royalton were unique for the couple, and the paintings that Edward made there were atypical within his total body of work. This was during the Great Depression, when farmers were seeking to make extra income by renting out rooms to tourists—indeed, tourism was being promoted by the state as a way to build the economy.

Driving on Route 110, just north of the intersection with Route 14, the Hoppers came upon the sign for Wagon Wheels, a dairy farm owned by Robert Arthur Slater and his wife, Irene, who lived there with their seven-year-old son. The Slaters’ advertised “Guests made to feel at home…. Abundance of fresh farm products. Home cooking.” The Hoppers boarded there for several weeks in the summer of 1937 and returned again in 1938, staying for nearly a month, until the great hurricane of that year destroyed the landscape.

From a hillside field next to the farmhouse, Edward painted the most well-known of his Vermont watercolors, "First Branch of the White River." Like his other White River paintings, it is a “pure landscape,” a bucolic scene without people or buildings, a rarity for Hopper. Vermonters will see in these paintings colors that accurately reproduce the distinctive blues and greens of the Vermont landscape, colors that are a departure from Hopper’s usual palate.

In South Royalton he turned away from the architectural forms that are hallmarks of many of his paintings, producing only one work that might be considered typical for hm, a watercolor of the Slaters’ sugar house. One of my artist friends has commented that the watercolors were “vacation paintings” for Hopper, an opportunity to relax in a place where he clearly found beauty and to work in a medium that allowed him the freedom to paint outdoors, with no pressure to produce something marketable.

Edward Hopper was known to be a silent, solitary man. But this does not seem to have been the case during his time with the Slater family. The late Robert Alan Slater—who was seven years old when the Hoppers stayed with his family—remembered him as being warm and friendly. Bob told me that Hopper had tried to milk a cow, albeit unsuccessfully, and that he followed his father around during chores and otherwise engaged with activities on the farm. In addition, Jo Hopper’s diaries, with detailed entries written during the weeks at Wagon Wheels, reports Edward’s making a paper model of Irene Slater’s display for the annual show of the South Royalton Garden Club. And finally, the Slater family owns a pen-and-ink drawing of the Wagon Wheels farmhouse that was made by Edward as a label for Irene Slater’s business cards, maple bon-bon boxes, and maple syrup tins.

All of these activities bespeak a special relationship between the farm family and the New York artists, a friendship that persisted over the years through correspondence between Jo and Irene. In 1966, at age eighty-three, Jo was still writing to Irene of “Happy memories in Vt. …Grand to have known you…& all things that had come to surround you.” We can surmise that the words of the gregarious Jo also stood in for those of her more silent husband.

Hopper died in 1967: what can art (or Hopper) aficionados take from his body of work and his summers here in Vermont?

For Hopper aficionados, a look at the Vermont watercolors will expand knowledge and understanding of the breadth of the artist’s interests and talents, which extend far beyond the monumental oils like Nighthawks. The story of Edward’s and Jo’s sojourns on the farm, and their relationship with the Slater family, also reveals the more human side of the man who is too often stereotyped as cold and anti-social.

Vermonters, even those who are not familiar with Edward Hopper’s more famous works, will recognize in his Vermont watercolors a landscape that they know and cherish. Unfortunately, these works are now widely scattered among private and museum collections, and as fragile watercolors, they are rarely displayed. The best of them, "First Branch of the White River," can be viewed on the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston's website.