Barre's homemade "second wine"

By Louisa Braun, Mario D. and Rose T. Lorenzini Fellow

Vermont is one of the states with the longest-running histories of alcohol prohibition, second only to Maine. In 1853, the state enacted a statewide prohibition, which remained on the books until 1902, when the legislature enacted a local option. That law allowed individual towns to vote annually on whether to begin issuing liquor licenses or remain dry by enforcing a total prohibition of alcohol. The City of Barre voted to remain largely “dry”, with only six exceptions: 1903, 1904, 1907, 1916, 1917, and 1918. In 1919, prohibition was established nationally with the 18th amendment, nullifying Vermont’s local option law.

Nationally, the temperance movement was rife with anti-immigrant sentiment. The industrial revolution had brought a significant influx of European immigrants to the United States, and anti-immigrant messages spread across the country, characterizing immigrants as dirty, lazy, and drunk. The Protestant-led temperance movement particularly targeted Catholic immigrants, whose religious services used wine. By 1914, almost one quarter of Barre’s population was Italian immigrants, and many opposed prohibition, in part because of the discrimination they faced because of its enforcement.

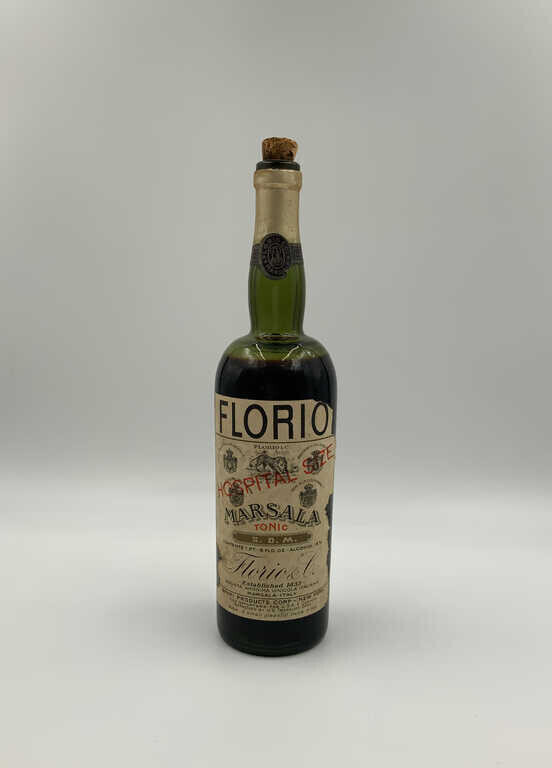

The Italian immigrant community in Barre made both wine and grappa at home to drink and sell, and imported and distributed alcohol from across state lines. The bottle pictured on the right is a part of the Vermont Historical Society collections and was once used by the family of Celeste and Armida Bianchi, first generation Italian immigrants who resided in Barre. It was originally filled with Marsala, a fortified wine made in Sicily, but was then reused by the family as a bottle for homemade grappa, which remains in the bottle to this day. Grappa is made by distilling the seeds, stalks, and stems of grapes left over from the winemaking process, and is sometimes called “second wine”. Grappa was particularly popular during prohibition because it increased the quantity of alcohol one could make at home from wine grapes, and has a higher alcohol content than wine.

Many Italian immigrants in Barre had cut ties with the Catholic church and were largely atheistic, but the widespread stereotypes of immigrants was enough to made the Barre community targets for prohibition enforcement. Between 1895-1914, more than half the liquor cases brought to court in Barre were against Italian immigrants, who made up less than one quarter of the population. In 1910, Benjamin Gates, the States Attorney for Washington County, brought detectives from Boston to infiltrate the Italian community in Barre, writing that “we desire to get evidence against places occupied primarily by Italians”. The two detectives found little evidence of illegal liquor activity, and none against Gates’ prime suspect.

Women were particularly discriminated against when it came to liquor licenses. Barre’s granite industry meant that many stonecutters died at a young age of a lung disease called silicosis, prompting their widows to find other sources of income. Many of the Italian and Scottish women opened boarding houses in their homes for granite workers, and supplemented that meager income by selling alcohol. Licensure might have provided relief to these women and their families, but in Barre’s six years of licensure, not a single woman was granted a liquor license, and many were arrested.

The discriminatory enforcement against Barre’s immigrant community helped to fuel the already existing opposition to prohibition. The community wasn’t particularly religious: in 1916, an Italian Baptist missionary named Antonio Mangano arrived in Barre and wrote that everywhere he went he was told, “You must not talk of religion here, for the Italians will hoot you out of town”. While what religious objections existed in town were a factor, their opposition to prohibition was also influenced by the predominant political views in their community, anarchism and socialism.

Barre was home to a significant anarchist community. Luigi Galleani, a prominent Italian anarchist, ran an influential anarchist newspaper called the Cronaca Sovversiva. In March 1908, when Barre voted to return to total prohibition, the Cronaca published a response, examining the flaws of the city’s licensing policies, and stated that the return to total prohibition was a mistake made by “the naive who in the laws of privilege seek the solutions to problems that only freedom can face and solve”[1]. Anarchist ideas of freedom clashed with both prohibition and regulated licensure, and helped turn many Italians in Barre against both policies.

The Socialist faction of Barre’s Italian immigrants was robust and powerful, with a dedicated Socialist Labor Party Hall, and a comprehensive mutual aid society, the Mutuo Soccorso. They argued that as long as there was profit to be made from alcohol, its production and consumption would not cease, and proposed that if one wanted a decrease in liquor consumption, the answer was not the prohibition of alcohol but instead the destruction of capitalism.

The legacy of Barre’s Italian immigrant community lives on today through the events held at the still-standing Socialist Labor Party Hall, dinners hosted by the still-active Mutuo Soccorso, and the carved granite statues that fill the city’s parks and cemeteries. Grappa is scarce, as outside of prohibition, most people prefer to drink first wine, not second, but Italian wines of many other varieties remain a staple in the Italian restaurants and grocery stores that dot downtown Barre.

[1] Cronaca Sovversiva (Barre, Vermont), Sat March 07, 1908, pg 4 - via Newspapers.com

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2023 issue of our member magazine, History Connections. To get it and support the Vermont Historical Society, sign up as a member.